When a group of cyclists were asked to ride to the point of exhaustion, they lasted 18% longer when the clock (secretly) ran 10% slow. In other words, ‘maximum effort’ is a psychological, not physical, limit.

Great expectations

Beliefs have the power to shape reality.

A fear of heights doesn’t just change our emotions – it changes our perceptions. People who are scared of heights will, quite literally, see the same height as larger than those who aren’t.

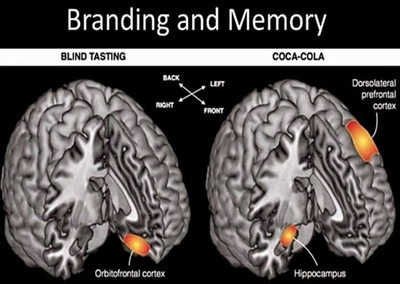

In 2003, neuroscientist Read Montague added an FMRI twist to the Pepsi Challenge. In a standard blind taste test, the brain region associated with seeking reward was highly active, and Pepsi still came out on top. But things changed when volunteers were told what they were drinking. This time, Coke was the clear winner, and the area of the brain associated with thinking processes lit up. In other words, the expectation of drinking Coke made it more enjoyable.

Recent neuroscience studies have shown that our brain is predictive, not reactive. It’s, quite literally, powered by expectations. When we drink a glass of water it actually takes tens of minutes to reach the blood, but it instantly feels like our thirst is quenched – that’s because our brain predicts the restorative effect of water as soon as we drink it.

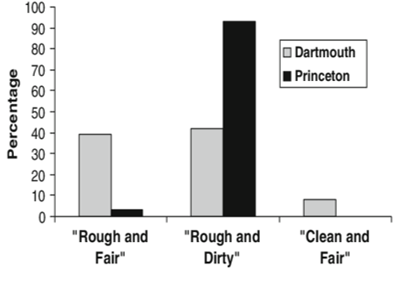

In 1951, when the Dartmouth football team played against Princeton, undergraduates at each college saw different versions of the very same game. In a post match survey, they both thought the other college had started the rough play and had been unnecessarily dirty. An early example of confirmation bias in action: we see what we want to see.

Superstitions are no joke. Basketball players are 12% more accurate with free throws following pre-performance rituals.

The prestigious Gilbert et Gaillard wine contest was won by a €2.50 bottle, disguised as a premium product with a fancy name (‘Chateau Colombier’) and an eye-catching label.

In a study, led by chef Heston Blumenthal, those who were told it was ice cream didn’t like it – the pink made them expect the taste of strawberry, not fish. But when it was introduced as ‘chilled salmon mousse’, to give people a fair warning, the reaction was much more positive.